In the quiet villages of rain-soaked Malenadu area in Karnataka, partitions develop into storytellers. Art in geometrical patterns bloom in pure hues. This is Deevaru Chittara, the normal art type of Deevaru neighborhood, an agrarian and matrifocal group dwelling within the area. For generations, their ladies have adorned partitions, doorways, material and ceremonial objects with symbols that talk of life, lineage and Nature. In their properties, Chittara survives not as a show, however as a dwelling language. Now, by way of the pages of a 200-page coffee table book, it reaches a brand new viewers. Deevara Chittara: the artform, the folks, their tradition (revealed by Prism Books), is the outcome of two-years of fieldwork and collaborations by three ladies: cultural researcher Geetha Bhat, documentary photographer Smitha Tumuluru and textile designer Namrata Cavale.

CFRIA Book workforce (L to R): Smitha Tumuluru, Namrata Cavale and CFRIA founder Geetha Bhat

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The trio travelled by way of Malenadu, overlaying many villages. “Every trip gave us something new,” says Geetha. “Sometimes, we felt we had missed asking a critical question and would go back.” She remembers an impromptu journey to doc Kere Bete, a mass fishing competition, when the river Varada recedes. “We were informed the night before and all of us hopped onto a train at dawn.” Smitha provides, “It was thrilling and terrifying to shoot in knee-deep waters with heavy cameras.”

Chittara is greater than only a visible art. It is a cultural documentation in pigments and patterns. Traditionally drawn throughout weddings, festivals and auspicious milestones, the motifs are geometric, delicate and symbolic. The ele or thread motif denotes familial ties. Nili kocchu, a criss-cross design represents the tatti (bamboo-strip partitions) or the sunshine filtering by way of the tatti. Poppali, a checkerboard sample evokes the joints of the home rafters and the celebrities, believed to be ancestors watching over the dwelling! “Even Patanga or peeti motif illustrates a butterfly perched on intersecting beams, hinting at the connection between Nature and art,” says Geetha.

It was Geetha’s first encounter with Chittara at an exhibition in Bengaluru’s Chitrakala Parishath 20 years in the past that planted the seed. The conversations with the artists led her to analysis on the art, tradition and way of life of this neighborhood. She later based the Centre for Revival of Indigenous Art (CFRIA) in 2008. Her fieldwork took her deep into the villages of Sagara, Sirsi, Soraba and Shivamogga (Shimoga) taluks, the place she acquired to see how the ladies returned from the fields, accomplished family chores and gathered to joyfully sketch the Chittara.

A fish-shaped border design ‘Bagilu chittara’ adorns the wall of a doorway at Kannada University Study Centre, Kuppali.

| Photo Credit:

Smitha Kalyani Tumuluru

Smitha, whose work explores arts, tradition, livelihood and gender, joined Geetha to {photograph} and co-write the book. “I told her I would not be able to pay a big fee,” Geetha remembers. “Smitha instantly agreed for pay-as-we-go. I could see her passion for the work.”

Moved by the aesthetic and symbolic depth of Chittara at a CIFRIA workshop, Namrata started designing tasks for CFRIA and got here on board in 2018. “This book was Geetha’s dream,” Namrata says. “Though I had designed scarves and murals for CFRIA earlier, this was my first experience at designing a book and every part of it felt meaningful. As a team, we aligned on core values and aesthetics,” shares.

The most outstanding expression is the Hase Gode Chittara, painted on the jap or northern partitions of properties. “It is considered auspicious,” says Geetha. Its magnificence is enhanced by enclosing it inside a three-sided border, the fourth is left naked, to convey guests are all the time welcome to their properties. Tiny collectible figurines of musicians usually mark the underside of this composition. The three-sided borders are additionally drawn on the entry door as Bagilu Chittara. The drawings are architectural of their essence, documenting the construction of the house and life. Metthina Chittara, for occasion, options in two-storied homes. While Namrata’s architect-mother might confirm the drawings representing the structural components of the home in Chittara patterns for the book, Smitha’s mathematician-father decoded the underlying geometry and symmetry within the motifs, highlighting the neighborhood’s intuitive brilliance.

The floral motifs — Chendu hoovu — seem as a single flower or torans (festive garland), whereas malli hoovu reveals up as a saalu (linear sample). A nesting chook, Goodina hakki, represents a feminine chook ready for her mate. “The madanakai (L-shaped wall brackets) on either side of the hase gode chittara not only represent the beams, but metamorphically indicate extension of families,” explains Smitha.

People rush into the shallow waters of Hecche panchayat lake in the course of the annual neighborhood fishing occasion — ‘kere bete’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Chittara additionally documents ceremonial objects corresponding to basinga and tondla, headgears for the bride and groom, painted as decorative motifs, whereas the Vastra Chittara, drawn on a material is used to wrap and retailer these objects post-wedding. The Tiruge mane, a carved pedestal used for putting choices, has its personal chittara illustration. The moole aarathi is drawn on the eechalu chaape (grass mat) throughout weddings. This sample is drawn as small as an 8-moole (8 nook) aarathi chittara to as huge as 64 or 160 cornered-patterns. “How these corners are connected is left to each artist’s creative interpretation,” says Namrata.

The 4 colors utilized in Chittara are rooted in ecology. Red is drawn from kemmannu (crimson earth) or raja kallu (crimson stone); white from soaked and floor rice or jedi mannu (white clay); black from roasted rice grains and yellow from the seasonal fruit of Guruge tree, a species of Garcinia. “Since yellow pigment comes from a specific seasonal fruit, it is used sparingly,” reveals Smitha, whereas the comb – pundi naaru, is made from a spread of jute fibre.

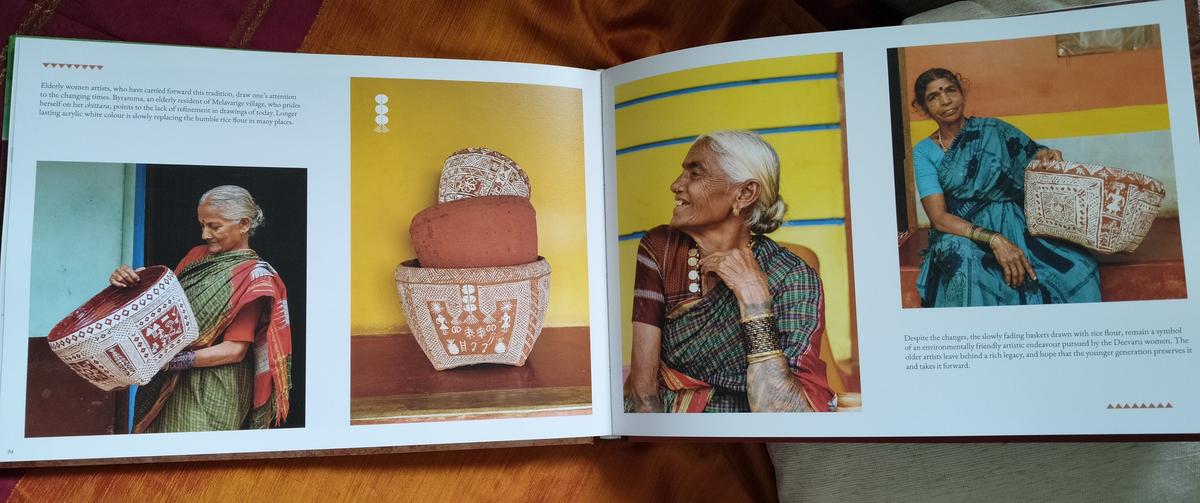

The book captures the life and tradition of the neighborhood

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

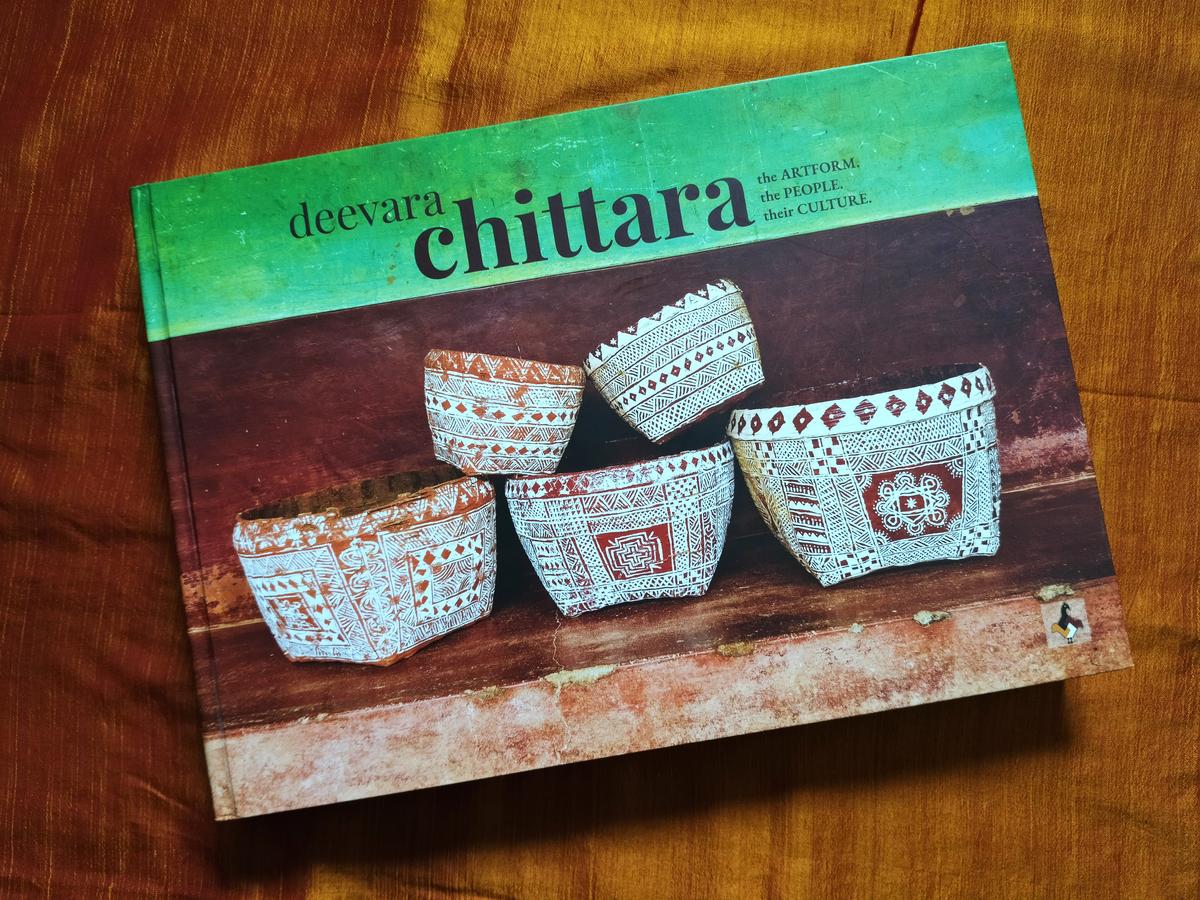

The book is a careful-curation of all these layers. Each part walks the reader by way of the historical past, motifs, rituals and evolving social landscapes of Deevaru neighborhood. “We have used colloquial Kannada for Chittara motifs such as ele, patanga, moole, poppali, but catalogued all in the glossary section,” says Geetha. Namrata’s design philosophy was to create respiratory area for the art. “This was not just about layout, but about reverence,” she says.

The book cowl

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The festive gala’s within the villages are tailored into therina chittara. The portray of theru (chariot) depicts the devaru (deity), positioned within the centre and folks pulling the chariot. Among probably the most attention-grabbing rituals of the neighborhood is Bhoomi Hunnime Habba, a competition that celebrates mom earth. Held on the complete moon earlier than Deepavali, this resembles a seemantha or child bathe for the earth. Deevaru ladies put together charaga (rice porridge with greens and greens), carry many delicacies in a Chittara-painted basket referred to as Bhoomanni Butti and provide parts not simply to one another, but additionally to birds, rodents, snakes — all the pieces that share the sector’s ecosystem. “For them, nature is god,” says Geetha.

CFRIA’s mission goes past the book. It conducts exhibitions, workshops and invitations ladies from the neighborhood to color partitions of various establishments. I want to take this lovely artform and dwelling custom and tradition of the Deevaru neighborhood to the surface world,” says Geetha.